Breasts 101: The Mechanics of Our Bodies

Let’s start here, ladies. Before we talk about cup sizes, before we talk about sagging, before we even whisper the word hypertrophy, we need to understand how our breasts are actually built. Not in a medical textbook way, not in a sterile hospital diagram way, but in a real-world, this-is-how-our-bodies-function kind of way. Whether you are an AAA or somewhere far beyond the alphabet, the same foundational mechanics apply to all of us. The difference is not the blueprint; it is how much load that blueprint is carrying.

Our breasts are not glued to our chest like ornaments. They are suspended, supported, and shaped by skin, connective tissue, fascia, and the pectoral platform beneath them. Muscle does not hold them up, no matter how many pushups we do. The support network is passive, which means gravity has a long-term relationship with all of us. Some of us feel that relationship more intensely than others. Understanding where our tissue begins, where it hangs from, and how it distributes its weight across our torso changes everything about how we think about bras, posture, comfort, aging, and even medical decisions.

This page is not about who is bigger or smaller. It is about structure. It is about why two women with the same bra size can look completely different. It is about why some of us project forward while others project lower. It is about why certain outcomes are predictable long before volume enters the conversation. When we understand the mechanics of our own bodies, we stop guessing and start making informed choices. That foundation comes first; everything else builds on top of it.

Where Our Breasts Actually Begin

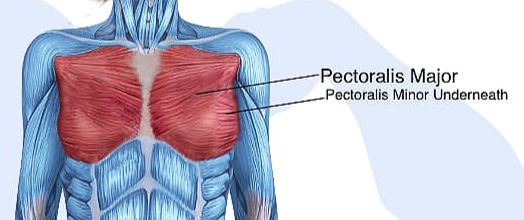

Before we talk about shape, size, or anything that hangs, we need to talk about the foundation our bodies give us. Our breasts do not float independently; they rest on a platform formed by our chest wall and the fascia over the pectoralis muscles. Think of this area as the stage beneath everything else. Some of us start higher on that stage, some of us begin lower, and that starting point quietly influences how our bodies carry weight for the rest of our lives.

A lot of women assume the muscle itself is holding everything up, but that is not really how our bodies work. The pectoralis is a base, not a hook. It gives our breasts a surface to sit against, a place where tissue can anchor and distribute load, but it does not lift or tighten the breast the way fitness myths sometimes suggest. What it does offer is structure, posture support, and a sense of where our tissue begins when we look at ourselves from the side or above. Once we understand that, a lot of confusion about why our breasts sit where they do starts to fade away.

One of the easiest ways we talk about this among ourselves is the axillary reference, the gentle line that runs across the lower edge of the armpit. For most of us, true breast tissue rarely begins above that line. That means two women with identical cup sizes can look completely different simply because one begins closer to the armpit while another starts further down the torso. This is not about right or wrong bodies; it is about understanding the blueprint each of us was given long before volume entered the conversation.

The two images above show this clearly. Even though the women have very different breast sizes, the axilla line sits in the same anatomical position on both bodies. That line does not move up or down based on cup size. It is a fixed surface landmark. What changes is how much tissue begins below it and how that tissue distributes across the torso over time.

When we look at photos of the pectoral area in motion, stretching, or supporting weight, what we are really seeing is the foundation reacting to gravity over time. Our bodies adapt, our skin stretches, and connective tissue learns to distribute load in ways that are unique to each of us. Starting here helps us speak the same language before we move on to folds, suspension, and the mechanics that shape how our breasts evolve as we age.

The Inframammary Fold

Now we talk about the fold. The inframammary fold, or IMF, is the natural crease beneath our breasts where the underside meets the chest wall. Every one of us has it, whether we notice it or not. It is not a flaw, not a cosmetic accident, not something invented by bra companies. It is a structural landmark, and once we understand it, a lot of things about our bodies suddenly make sense.

The IMF marks the transition point between supported tissue and suspended tissue. Above the fold, our breasts are closer to the chest wall and share more structural support from the fascia over the pectoralis. Below the fold, the tissue hangs more freely, relying on skin and connective fibers to manage gravity. The lower that the fold sits on our torso, the more of our breast mass is technically in suspension. That matters more than cup size ever will.

What we want you to notice in these two photos is this: the fold itself is almost in the same place on both women. That crease along the side of the chest, right where the breast meets the torso, is the inframammary fold. It is a structural landmark. It does not automatically drop just because the breast becomes longer or more pendulous. The woman on the right has much more tissue extending below that fold, but the anchor point along the ribcage is strikingly similar.

This is where so many of us get confused. We tend to assume the IMF is at the bottom of the breast, but it is not. It is the base where the breast transitions from the chest wall to the suspended tissue. Everything that hangs below it is dependent on skin, connective tissue, and gravity. Understanding that distinction helps us separate attachment from length, and that clarity becomes incredibly important as we move into discussions about density, sagging, hypertrophy, and long-term structural changes in our bodies.

This is why two women with the same bra size can look completely different. One may have most of her volume sitting above or near her IMF, appearing round, projected, and dense. Another may have more of her volume sitting below the fold, appearing longer or more distributed. The total volume might be identical, yet the visual impression and mechanical strain are not the same at all. When we say structure matters, this is exactly what we mean.

It is also important to understand what the IMF does not tell us. It does not determine our worth, our femininity, or how attractive we are. It does not mean one body is better engineered than another. It simply reflects how our connective system developed and how our bodies manage load over time. Some of us were born with a higher fold, some lower. Neither is wrong, but each carries different long-term implications.

In both stationary examples, we can see that the lateral IMF forms a consistent double arc that exists independently of body orientation. Whether a woman is upright or inverted, gravity simply redistributes the volume of the breast; it does not relocate the anatomical fold itself. What changes is the way the tissue drapes around that foundation, which can make the arc appear higher, lower, or more pronounced depending on movement, density, and projection.

These images help us understand that the IMF is not defined by where the breast hangs at any given moment, but by the structural crease where the breast meets the torso. When volume lifts, swings, or shifts, the underside fold briefly becomes more visible, revealing that the same curved path exists across different positions. Seeing the arc repeated across multiple angles gives us a clearer visual language for identifying the IMF without confusing it with the moving edge of breast tissue.

In these motion examples, our breasts may lift, swing, or shift dramatically with movement, yet the inframammary fold stays anchored in the same place along the torso. Comparing these side by side helps us separate what moves from what stays constant, reminding us that while tissue is dynamic, the fold itself remains the steady foundation of where our breasts attach.

When we begin to pay attention to where our IMF sits, we start seeing patterns. We understand why certain bras dig, why others gap, and why some of us feel heavy even when our cup size sounds moderate. We see how gravity interacts with our individual blueprint. Before we ever discuss hypertrophy, sagging, or extreme growth, this fold quietly tells a story about support, suspension, and how our bodies carry what they were given.

Breast Base Height

When we talk about high set or low set breasts, we are not talking about sagging, cup size, or how far tissue hangs. We are talking about the breast root, the physical footprint where our breast tissue attaches to our torsos. This attachment point is structural. It exists whether we are an AAA or a ZZ. The bottom of that footprint is the inframammary fold, and its vertical position relative to our ribcage determines whether we are high set, medium set, low set, or very low set.

A high set breast root sits higher on the torso, meaning the IMF is positioned closer to the armpit line and upper ribcage. A low-set root sits farther down the torso, even before any visible sagging occurs. This is why two women with the same cup size can look completely different. The difference is not volume alone; it is where that volume is anchored.

High Root Position Medium Root Position Low Root Position Very Low Root Position

Breast root position is independent of hang. A woman can have self-supported breasts and still be naturally low-set. Another woman can have very pendulous tissue and still technically be high-set at the root. The root is the base. The hang is what gravity does to the tissue over time. Separating these two concepts is critical if we want to understand structure instead of just appearance.

Root height also influences how our bras behave. High-set roots often struggle with tall side wings or wires that poke into the armpit. Low-set roots often require more strap adjustment and different vertical proportions. When a bra feels “off” even in the correct size, it is often a root issue, not a cup issue. Our bodies are not wrong; the geometry is simply different.

As you look at the images below, notice that the dashed line marking the IMF moves progressively lower from a high set to a very low set. The breast tissue above that line may be small or full, lifted or relaxed, but the line itself tells the structural story. This is the foundation we build on before we ever discuss hypertrophy, growth patterns, or long-term changes.

IMF Length and Variation

Every one of us has a natural IMF length, and just like base height, it exists on a spectrum. Some women have a short distance from the axilla line down to the inframammary fold, often measuring in the low two to three inch range. Others naturally sit in the four to six-inch range, and some are even longer without anything being “wrong.” This is not about size. A small A cup and a full G cup can share nearly identical IMF lengths. The fold is structural, not volumetric. It tells us where the breast is anchored, not how much tissue is hanging from it.

Short

IMF

Long

IMF

Where things become more dramatic is when significant volume enters the picture. In cases of very large breasts, especially on a naturally low-set frame, gravity interacts with that attachment over the years. The IMF itself does not float freely, but the skin and connective support above it can stretch, and in extreme hypertrophy, the fold can migrate lower over time. A woman can develop an IMF length exceeding twelve inches, placing her fold just above the upper abdomen. That does not mean all twelve inches are dense tissue. It means the anchor point itself has descended as her body adapted to the load.

Understanding this variation helps us separate anatomy from assumption. A long IMF does not automatically mean massive breasts, and massive breasts do not automatically mean a long IMF. What matters is how much tissue is suspended from that attachment zone. When we learn to measure and observe this correctly, we stop describing breasts only by cup letters and start understanding them as structures supported by a foundation. That shift in thinking changes everything.

There is an underlying correlation that large breast volume on a short IMF would typically result in more protruding, denser breasts, unless the breast volume is so significant, like macromastia, where it overpowers the metrics and expands downward, as the examples in the Short IMF set above. Whereas a naturally low IMF with large breast volume typically results in a more pronounced initial and gradual sag rate. The example woman on the right with naturally low IMF has fatty, floppy breasts that sag, compared to the denser examples in the Short IMF. Many factors would be at play for each example, but the IMF distance plays a significant role in determining potential outcomes of breast developmental mechanics.

The Asian Boomerang

Now and then, we see something in our own bodies, or in other women’s bodies, that does not fit neatly into the textbook diagrams. The Boomerang is one of those things. This is a term that we created to describe the smooth, continuous underside contour that forms a clean arc from one side of the chest to the other, almost like a drawn line, even though the true inframammary fold sits higher. In certain positions, it can make a chest appear almost an amorphous mono-breast. This is not sagging, and it is not simply volume. Asian Boomerangs can be formed as a tension pattern across the lower breast envelope. Bra size does not seem to be a factor; we have seen varying boomerangs on as small as 34C-cup fatty breasts.

In our extensive collective experience, we have seen boomerangs overwhelmingly among East Asian women compared to other women we have encountered, which we find both fascinating and puzzling. Several factors may contribute to this. Differences in dermal thickness, collagen distribution, and connective tissue elasticity can influence how skin and underlying fascia respond to movement and gravity. Chest wall shape, ribcage curvature, and natural base height patterns may also play a role in how the lower contour presents during lift or motion. Hormonal patterns, body fat distribution tendencies, and genetic variation in ligament structure could further affect how this arc forms and whether it appears as a continuous line. However, boomerangs are more common in Asian women with larger, fatty breasts, but multiple factors are at play.

What makes The Asian Boomerang so fascinating is that it is not the inframammary fold itself. We can lift the breast and clearly feel where the actual fold attaches to the torso, and it sits higher than this arc, especially toward the center. The Asian Boomerang forms below that attachment point, almost like a suspended bridge of tissue responding to tension, density, and skin structure. When the breasts are supported, lifted, or positioned in certain ways, that underside contour becomes unmistakably clean and unbroken, a visual line that exists independent of true root height. This occurs most commonly when lying flat or slightly propped up from the lying position, as seen in the examples above.

In our collective experience, Asian Boomerangs show up far more frequently in some body types than others, even when bra size is identical. Two women can share the same cup size and volume, yet only one can create this smooth, continuous underside arc. That tells us this is not about size. It is about how tissue is distributed, how skin holds tension, and how the lower envelope interacts with gravity. The Asian Boomerang is simply another reminder that breasts are not one template repeated across women; they are structural systems shaped by attachment, density, and the unique architecture of each body. The effect tends to make the breasts pancake and appear far flatter than they actually are. While we have seen this occur on some other ethnicities, it seems overwhelming that there is an interplay between the lateral IMF crease and the body position on certain Asian women.

How Base Height and IMF Interact

When we combine base height with IMF length, we finally see the real blueprint of how our breasts sit on our bodies. Base height tells us where our tissue begins on the torso. IMF length tells us how far that attachment extends downward before the fold forms. Together, these two measurements define the structural footprint of our breasts. Size alone cannot do that.

A high base height paired with a shorter IMF often creates a compact, concentrated mound. The tissue is anchored higher on the chest and supported across a shorter vertical span. Even with moderate volume, this combination tends to look rounder and more projected because the mass is distributed over less vertical real estate. This is why two women with the same cup size can look completely different in profile.

Now take a low base height with a longer IMF. The attachment zone stretches further down the torso before the fold. The tissue has more vertical surface area to occupy. If volume increases, it spreads and descends rather than projecting forward. This does not mean better or worse. It simply means the architecture favors elongation over projection.

When volume becomes significant, these differences amplify. A high base with a shorter IMF may feel denser and heavier in a compact area. A low base with a longer IMF may distribute weight across a greater span, often leading to more pendulous presentation over time. The total breast mass could be identical, yet the mechanical behavior differs because the attachment geometry is different.

This is why we always separate size from structure. Cup letters describe volume. Base height and IMF describe architecture. When we understand how those two interact, we stop comparing ourselves blindly and start understanding why our bodies behave the way they do.

Why Size and Attachment Are Not the Same

We have to say this clearly because the world has confused it for decades. Breast size and breast attachment are not the same thing. A woman can have small breasts that are low-set. A woman can have very large breasts that are high-set. Size is volume. Attachment is a structure. They live in completely different categories, even though people constantly mix them.

When someone says “she has big breasts,” they are usually talking about projection or length. They are looking at how far the breast extends outward or downward. What they are not seeing is where that breast actually begins on the torso. Two women can both be a 34F. One can carry her volume high and compact with a shorter IMF. The other can carry the same volume lower altitude with a longer IMF. On paper, the size matches. Structurally, they are completely different. Many Asian women that people would instantly dismiss as having small breasts or being flat-chested likely have high C cups or D cups.

These two women appear to have very different-sized breasts. Yet they wear identical bras....

What you are seeing here is not a difference in size; it is a difference in structure. These two women wear the same bra size and carry the same approximate breast volume, yet their bodies present that volume in completely different ways. Base height determines where the breast sits on the torso, IMF length determines how much of that volume hangs versus anchors, and tissue density determines how far forward that volume projects. When we understand those three elements together, we stop judging breasts by appearance alone and start recognizing how attachment shapes everything we see.

Asians are just built different. Both women are 34F

This is where confusion about sagging begins. A low-set woman with moderate volume may appear softer or more pendulous earlier in life, not because she has “worse skin” or weaker ligaments, but because her attachment point began lower and her IMF gives the tissue more vertical runway. A high-set woman with the same volume may appear firmer for longer simply because there is less vertical drop available.

Volume does not dictate position. Position does not dictate volume. And neither automatically predicts future changes without considering the other. This is why cup size alone tells us almost nothing about how a breast will age, behave in motion, or respond to gravity over decades.

Once we separate these ideas in our minds, everything becomes easier to understand. Sagging is not random. Density is not random. Distribution is not random. Our structure sets the stage, and volume interacts with that structure. That is the language we are learning here together.

Copyright © 2013 - 2026 Sakura Geisha, LLC. All Rights Reserved. Terms of Service Privacy

Client services available in CS, DE, EN, ES, FR, HR, HU, IT, RO, RU, SR, SV, VI , 國語, 粵語, 臺語, 日本語, 한국어